Bådmagasinet har her fredag morgen kl. 06.00 modtaget en længere pressemeddelelse fra Vestas 11 Hour Racing, som vi vælger at bringe som modtaget, på engelsk.

Sagen får ikke følger ved de Kinesiske myndigheder og politi, hvorfor teamets skipper Mark Towill gerne vil udtale sig om ulykken.

Det ser ud som om der har været en del vanskeligheder omkring kommunikationen under redningsaktionen - vi følger op senere på dagen, på dansk ;-)

I første om gang er Vestas tilbage i gamet...

----------

VESTAS 11TH HOUR RACING READY TO REJOIN VOLVO OCEAN RACE

Team will participate in next Southern Ocean leg around Cape Horn and onwards to Brazil

Auckland, New Zealand.

When Vestas 11th Hour Racing rejoins the Volvo Ocean Race for the grueling Leg 7—from New Zealand, across the Southern Ocean, past Cape Horn and into Brazil—the crew will do so with a mixture of heavy hearts and anxiousness.

The team hasn’t raced since the collision in the latter stages of Leg 4, during the final approach to Hong Kong.

Just after 0100 hours on the morning of January 20 (local Hong Kong time), Vestas 11th Hour Racing was involved in a collision with a fishing vessel. Shortly after the accident, nine Chinese fishermen were rescued, however, one other very sadly perished. The Vestas 11th Hour Racing crew were not injured, but the VO65 race yacht suffered significant damage to its port bow. See Q&A with Mark Towill, skipper of Leg 4 for additional information on the incident.

The loss of a life still weighs heavily on the minds of Mark Towill and Charlie Enright, the co-founders of the team, and every other team member. “On behalf of the team, our thoughts and prayers go out to the deceased’s family,” said 29-year-old Towill. Out of respect for the process, the deceased and his family, the team has remained silent throughout the investigation.

Towill was skipper on Leg 4 because Enright had to sit out due to a family crisis. During Leg 3, from South Africa to Australia, Enright’s 2-year-old son had been admitted to the hospital with a case of bacterial pneumonia. Immediately before the end of Leg 4, Enright traveled to Hong Kong to greet the crew at the finish line, but instead had to play an active role in the crisis management process from the shore.

“I have been asked if it would have been different if I was onboard. Definitely not,” said Enright. “The crew has been well trained in crisis situations and performed as they should. They knew what to do and I think they did a phenomenal job given the circumstances. There comes a point when family is more important than the job you’ve been hired to do and I was at that point. I did what was best for my family.”

“The team was engaged in search and rescue for more than two hours with a compromised race boat,” Enright said. “I’m very proud of our crew. We were in a very difficult situation with the damage to the bow, but everyone acted professionally and without hesitation,” added Towill.

Despite the badly damaged bow, Towill and the crew of the stricken Vestas 11th Hour Racing boat carried out a search and rescue effort, which culminated in a casualty being retrieved and transferred to a helicopter, with the assistance of Hong Kong Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre.

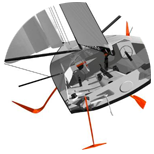

The Vestas 11th Hour Racing VO65 was shipped to New Zealand from Hong Kong on January 28. A new port bow section was laid up over a VO65 hull mold at Persico Marine in Italy and then sent to New Zealand, where it was spliced to the hull of the team’s VO65 in the past two weeks.

Enright and Towill both complimented team manager Bill Erkelens, who has played a central role keeping the team together since the accident. Erkelens put together Enright and Towill’s program in the 2014-’15 Volvo Ocean Race and he was the first person they hired for the current team.

The team hopes to relaunch their VO65 in the coming days and will then spend some time practicing and possibly complete an overnight sail.

In the 2014-15 Volvo Ocean Race, Enright and Towill’s crew led the fleet around Cape Horn by 15 minutes. It had been two weeks of thrilling racing from New Zealand, highlighted by 50-knot winds and a jibing duel along the ice boundary and a tight port/starboard crossing.

“That was an experience that’s still very fresh in my mind,” said Enright. “It was a hair-raising leg, with lots of maneuvers and heavy conditions. We’ll have to be on our toes again because the Southern Ocean demands respect. I imagine once we get a couple of days out of Auckland we’ll settle into the normal pattern of life at sea.”

Leg 7 of the Volvo Ocean Race, approximately 6,700 nautical miles to Itajaí, Brazil, is scheduled to begin March 18. Prior to that the New Zealand In-Port Race is scheduled March 10.

Q&A WITH VESTAS 11th HOUR RACING CO-FOUNDER, MARK TOWILL

Vestas 11th Hour Racing co-founder, Mark Towill, spent time at home with family and friends after departing the Volvo Ocean Race Hong Kong stopover where the team’s VO65 was involved in a tragic accident with a fishing vessel. Towill has now regrouped with the team and their VO65 yacht in Auckland, New Zealand, ahead of the next leg of the race. The team has now been informed that investigations by the Hong Kong and mainland China authorities will be closed shortly with no further action to be taken. As a result, Towill gives us his account on what happened in the early hours of January 20 in the approach to Hong Kong.

What happened as you approached the finish line of Leg 4?

We were about 30 nautical miles from the finish, and I was at the navigation station monitoring the radar and AIS (Automatic Identification System), and communicating with the crew on-deck through the intercom. I was watching three vessels on AIS: a cable layer, which we had just passed, a vessel farther ahead moving across our bow and away, and a third vessel identified as a fishing vessel. There were a number of additional boats on AIS, many of them fishing vessels, but these three were the only ones identified in our vicinity.

What were the conditions like? What could you see?

It was a dark and cloudy night, with a breeze of around 20 knots and a moderate sea state. As we approached the fishing vessel that we had identified on AIS, the on-deck crew confirmed visual contact – the fishing vessel was well lit – and we headed up to starboard to keep clear. I was watching AIS and communicating the range and bearing to the crew. The crew confirmed we were crossing the fishing vessel when, before the anticipated cross, there was an unexpected collision.

What happened immediately after the collision?

So much happened so fast. The impact from the collision spun us into a tack to port that we weren’t prepared for. Everyone who was off watch came on deck. Everyone on our boat was safe and accounted for. We checked the bow, saw the hole in the port side and went below to assess the damage. Water was flowing into our boat through the hole, and there was concern over the structural integrity of the bow.

How did you control the ingress of water?

We heeled the boat to starboard to keep the port bow out of the water. The sail stack was already to starboard and the starboard water ballast tank was full. We also kept the keel canted to starboard. We placed our emergency pump in the bow to pump water overboard. We were able to minimize the ingress, but the boat was difficult to maneuver because it was heeled over so much.

What actions did you take immediately after getting your boat under control?

It took roughly 20 minutes to get our boat under control, and then we headed back towards the location of the collision. Upon arrival, several people on a fishing vessel nearby were shining lights to a point on the water. Our first thought was that they could be looking for someone, so we immediately started a search and rescue. After some time searching, we eventually spotted a person in the water.

Who were you in communication with? Did anyone offer assistance?

We tried to contact the other vessel involved in the collision, and alerted race control straight away. When we initiated the search and rescue, our navigator immediately issued a Mayday distress call over VHF channel 16 on behalf of the fishing vessel. There were many vessels in the area, including a cruise ship with a hospital bay, but they were all standing by.

Communication was difficult. The sheer volume of traffic on the radio meant it was hard to communicate to the people we needed to. Not many people on the VHF were speaking English, but we found a way to relay messages through a cable laying vessel, and they were able to send their guard boat to aid in the search and rescue.

How was the casualty retrieved?

Difficult conditions and limited maneuverability hampered our initial efforts to retrieve the casualty. The guard boat from the cable layer provided assistance and every effort was made from all parties involved in the search and rescue. We were finally able to successfully recover the casualty after several attempts. When we got him aboard, our medics started CPR. We alerted Hong Kong Marine Rescue Coordination Centre that we had the casualty aboard and they confirmed air support was on its way. He was transferred to a helicopter and taken to a Hong Kong hospital where medical staff where unable to revive him.

Did any of your competitors offer assistance?

Dongfeng Race Team offered assistance. At the time, we were coordinating the search and rescue with multiple vessels, including the cable layer that had a crewman who spoke Chinese and English and was relaying our communication. We advised Dongfeng that they were not needed as there were a number of vessels in the area that were closer.

Team AkzoNobel arrived while the air transfer was in effect. Race control requested that they stand by and they did, and we later released them once the helicopter transfer was complete.

What happened after the search and rescue procedure was completed?

Once we knew there was nothing more we could do at the scene of the accident, we ensured our boat was still secure, and informed Volvo Ocean Race that we would retire from the leg and motor to shore. We arrived at the technical area nearby the race village and met with race officials and local authorities to give our account of what happened.